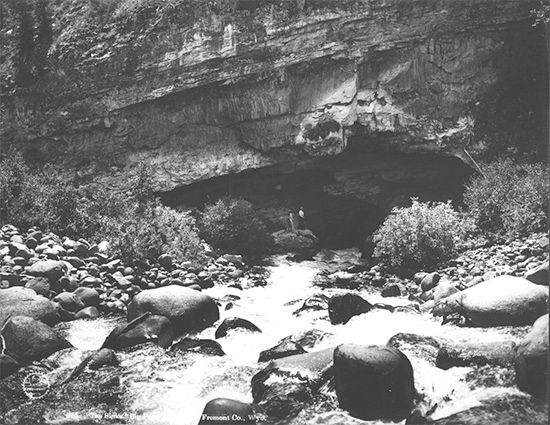

From the time the Ice Age glaciers retreated about 10,000 years ago people have journeyed into Sinks Canyon. The canyon is a natural pathway into and over the southern Wind River Mountains. For thousands of years people and wildlife have moved up from the Lander Valley, through the canyon and over the mountain passes to the other side of the range and back again. Wildlife migrated seasonally following forage and prey. Prehistoric people came to the canyon to hunt Bighorn sheep, quarry valuable stone to make tools and pick berries. Archaeological evidence shows people camped in the canyon 9,000 years ago. These people probably used the canyon mostly in the fall when wildlife were migrating and berries ripening. Native American use of the canyon continued over the centuries with tribes such as the Crow, Shoshone and others using the canyon in much the same way. The name Popo Agie is a Crow Indian word, which most people agree means “gurgling river.”

European explorers, fur trappers, cattlemen and settlers followed in more recent times. Mountain men trapped beaver in the Popo Agie; lumber mills and stone quarries in the canyon helped build the new town of Lander in the late 1800s. Cattle and sheep outfits moved their herds through the canyon in the spring to reach lush mountain meadows. People visited the canyon for its scenic and recreation values since the valley was settled. People have always been amazed by the beauty of the canyon and sight of the Sinks and Rise. The upper half of the canyon is protected as part of the Shosohone National Forest in 1891. The lower canyon was preserved by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department in the 1930s as wildlife habitat. The lower part of Sinks Canyon became a Wyoming State park in the early 1970s. Today people still come to marvel at the natural wonders found here, and use the canyon to reach the Wind River Wilderness.

Early Geological History

The view down into the canyon

The massive glaciers and ice sheets of at least 3 major ice ages over the past million years carved the rugged canyons and sharp peaks of the Wind River Range. The billions of gallons of melting water from the ice continued to shape Sinks Canyon. The glacial ice and rushing river created the corridor to the mountains.

Sandstone cliffs on the south facing slope

Early Human History

Humans first arrived in what is now Wyoming approximately 11,000 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age. These early people were hunter-gatherers who roamed the region hunting many now extinct species such as the mammoth.

The first firm evidence of humans in the canyon dates to 9,000 years ago. Archaeological digs in the canyon have found hearths and tools carbon dated to that age. These prehistoric people used the canyon to travel from the valley into and across the mountains. Along the way they hunted, fished, collected berries, wood and plants and quarried chert, a hard flint-like material found in deposits in the canyon. It is likely the use of the canyon was seasonal.

These early people left only a few traces of their presence. Projectile points and other artifacts such as pipes and stone axes have been found and flake beds where they chipped chert into tools are scattered around the canyon.

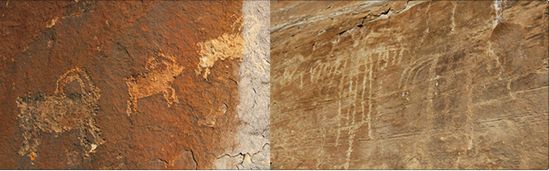

There are also a small number of petroglyphs and pictographs on some of the rock faces in the canyon. The oldest petroglyphs, or pecked rock art, are approximately 5000 years old. The pictographs, or painted rock art, are probably only a few hundred years old.

A few petroglyphs and other archaeological evidence in the canyon show people have used the canyon for thousands of years.

Prehistoric people had a complex set of religious beliefs and their rock art probably played an important role in religious rituals. Some possibly referred to hunting magic, healing and vision quests. Interpreting what a specific piece of rock art means is nearly impossible. Much of the symbolism is highly personal and only the maker or his community could decipher it.

Prehistoric hunter-gather bands traveled Wyoming for the next several thousand years with new groups migrating into and through, either driving out or absorbing populations that lived in the area.

Around 1300 A.D. the ancestors of today’s Shoshone Indians migrated from the Great Basin to the west over South Pass and into the Green River Valley and Wind River Valley. The Crow people (also known as the Absarokas) arrived in northern and central Wyoming around 1500 from the northeast. These people lived as their ancestors had done for thousand of years. Both Crow and Shoshone hunted and lived in the Wind River Valley and used the canyon.

Around 1700 A.D. the Shoshone aquired the horse which had been introduced by Spanish explorers. The horse allowed the Shoshone to begin the transition to the Plains Indian Bison hunting culture. Since the Shoshone were among the few Native Americans with horses, they rapidly became a power on the plains conquering territory from Canada to Texas. To the East the Blackfeet, enemies of the Shoshone, aquired guns from traders. Now armed, they allied with other enemies of the Shoshone and drove the Shoshone into the mountains. By 1830 the Shoshone were living deep in the Rockies in Idaho and western Wyoming while the Crow, Blackfeet, Lakota and Cheyenne controlled the bison-rich central plains of the state.

The first white men to visit the Lander Valley and Sinks Canyon were trappers in search of Beaver Pelts, and it was the Crow Indians who greeted them. It is from the Crow language that we get the name Popo Agie, which most people believe means “gurgling river,” for the sound the water made going into the cave.

As the westward expansion of the United States continued the Shoshone allied themselves with the U.S. Government. Under the leadership of Chiefs Cameawhait and Washakie, the Shoshone regained some of their former territory, hunting and living in the Wind River Valley.

Chokecherries in the fall

All through this time the Crow, Shoshone and others used Sinks Canyon to hunt and travel. One use of the canyon that has remained unchanged for centuries is berry picking. The dark red chokecherry grows in abundance in the lower reaches of the canyon as do currants, gooseberries, sumac, Oregon grape and other berries. Even today native people visit the canyon in the fall to pick berries, collect sage and other plants.

After the fur trade faded (a rendezvous was held in the Lander Valley in 1829) the Oregon Trail pioneers moved through Wyoming on the way to the west coast from the 1840s through 1890s, but few, if any, migrants made it into the Wind River Valley north of the trail route.

In 1867 gold was discovered at South Pass and the boom was on. Towns sprang up and thousands of fortune seekers came to hunt for the metal. The boom didn’t last long though and soon residents of the “Sweetwater mines” region began moving down to the fertile valley to start farms and ranches to supply the U.S. Army forts built first in Lander, then at Fort Washakie to protect the newly founded Wind River Indian Reservation.

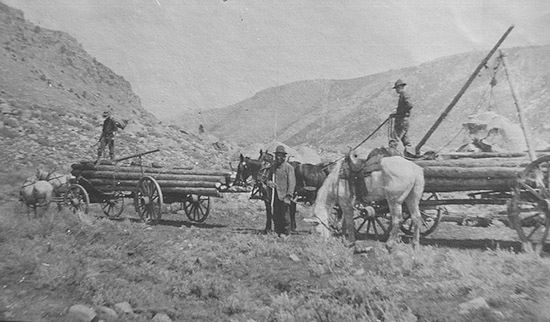

Sawmills

The town of Lander was founded in 1875 and soon sawmills were started to help build the town. Sam Fairfield is credited with building the first sawmill using logs hauled from Table Mountain. In 1876 Fairfield built a rough road into the canyon and moved his mill to Fairfield Hill in the canyon. In 1883 Ace Wilson opened his mill in Sinks Canyon. These early mills provided much of the timber to build the towns of Lander and Milford and many ranches and homesteads in the area. As the easily reached timber was cut down mills were built further back in the mountains: At the head of Sawmill Creek, Fry Meadows, Neff Park and Warthen Meadows. Logs from Warthens sawmill were used for railroad ties to help build the rail line from Casper to Lander in 1904. Today Warthen Meadows is covered by a large reservoir and is called Worthen meadows.

1900's

Early in Lander’s history cattle and sheep men used Sinks Canyon to move their animals into the high country to graze. The “Shoshone Stock Driveway” was the major cattle trail in the southern Wind River Mountains and was accessed through Sinks Canyon. The relatively easy grade, good water and grass and easy fords were, and still are, why stock is moved through the canyon from valley to the mountains.

Almost from the time Lander was settled people visited the canyon to sightsee, fish and camp. The road to the canyon was only a dirt wagon track and it was often a full days journey to get there, but many families would load up the wagon and spend the day visiting the Sinks and Rise and fishing along the river.

One of the most popular spots to stop was Bruces Campground, named for John Bruce, one of the earliest forest rangers in the area.

In 1895 W.O. Owens wrote: “The natural bridge of Virginia is quite insignificant in comparison with the great Sinks of the Popo Agie and no one visiting Lander should fail to see this great freak of nature.”

As the road improved over the years even more people visited the canyon. The Rise and its fish became such an attraction that the Mountain States Power Company built an overlook above the pool in 1947 so sightseers could safely see it. The canyon was also a popular spot for local outfitters to set up fishing and hunting camps to take “dudes” into the mountains.

It was about the 1930s when the canyon started to be known as Sinks Canyon. Previous maps and legal documents listed it as either Big Popo Agie Canyon (the little Popo Agie River flows out of the mountains through its own canyon near Red Canyon) or simply the Canyon. When inks Canyon came into common use many old timers protested saying Big Popo Agie Canyon was a more appropriate and beautiful name.

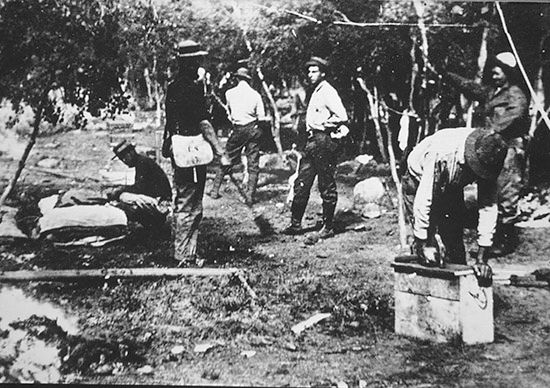

Crispin at his quarry in the canyon

The upper half of the canyon has an abundance of granite and from 1883-1930 stonemasons used this rock to create ornate headstones and provide foundations for Lander buildings. A 1928 article in the Lander Journal said “The finding of a granite of such fine quality right here in Lander has been greatly appreciated by many old timers whose sentiment has led them to give preference to the home product rather than ship in foreign stone.”

Howard Crispin is the name most associated with stone work in Lander. The Crispin quarry was a few hundred yards above Bruces Campground – Crispin would drill and blast chunks of granite from boulder along the river, then haul them to his stone shop in town where he would shape and polish them. Many older headstones in the Lander cemetery were created by Crispin from Sinks Canyon granite.

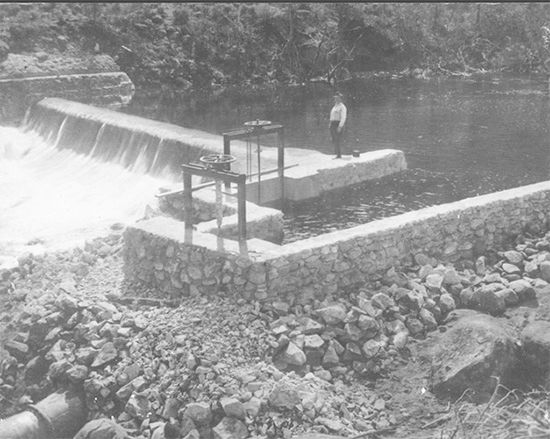

Hydro Electric Power

In 1919 E.D. Edwards organized the Sinks Canyon Hydro Electric Company and built the power plant at the Rise, and the dam and pipeline above the Sinks. Lander had electric power as early as 1893, provided by a coal and oil powered plant near the Lander mill on Main Street. The Sinks Canyon plant was cheaper, stronger, more reliable, and provided a steady source of power for Lander for many years. The original pipeline was made of redwood and the flow of water through the line to the two Pelton turbines in the power house generated 500 horsepower of electricity. Later the wood pipline was replaced by steel and in places segments of the old metal pipeline can still be seen. The steady electricity from the power plant provided another first – E.D. Edwards had one of the first radios in Fremont County. He ran his antenna to the top of the sandstone cliffs above the Rise and was able to pick up two radio stations, one in Denver and another in Omaha.

Sinks Canyon Hydro Electric was sold to Mountain States Power in 1928. Mountain States raised the dam a few feet to provide a stronger flow through the pipeline and added a third turbine to the power plant.

Pacific Power and Light Company took over operation of the plant in 1954 and soon after the Sinks Canyon operation was shut down. The plant was old and deteriorating, and cheaper power was available from Boysen Dam and Reservoir.

Today the old stone power plant sits empty at the edge of the Rise. The log residence that was the home of E.D. Edwards is now the park superintendent’s residence. The dam is being worn away by the river and portions of the old metal pipeline still peek through the sagebrush.

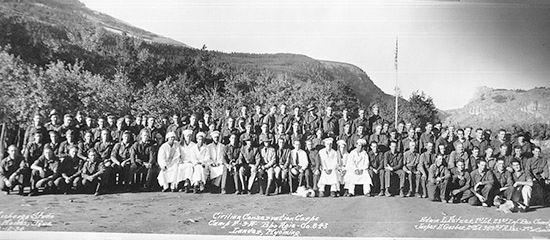

University of Missouri Geology Camp

The University of Missouri Geology Camp has been a part of Sinks Canyon history since 1911. The camp’s founder Edwin Branson visited the canyon in 1904 and was impressed by the wealth of geology and fossils in the area. Branson suggested it be used as a field camp when he became professor at the University of Missouri.

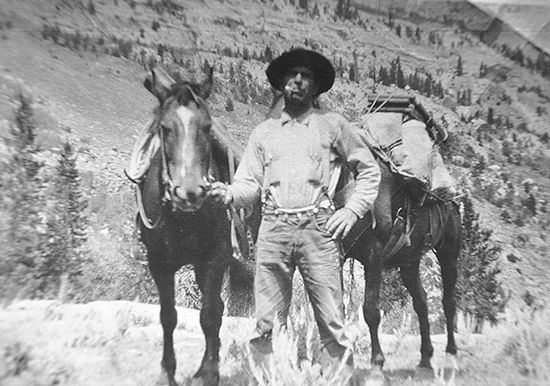

In 1911 Branson and 11 students traveled by train to Lander and then on horseback to Sinks Canyon, setting up the first field camp at the mouth of the canyon (in the area that is today’s Sawmill Campground).

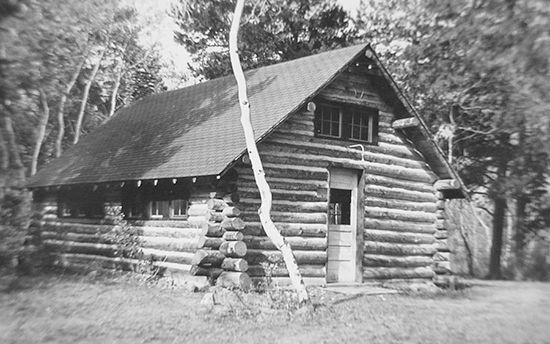

The University of Missouri Geology Field Camp has been in the canyon since 1915. Here students break camp, which was originally a tent camp at the mouth of the canyon.

The geology camp was a tent camp until 1929 when, with the support of the Forest Service, the camp was permanently located further up the canyon on an island in the river near the old Middle Fork Ranger Station and renamed Camp Lander. Over the next 20 years many log buildings were added, most built by students from the camp in exchange for room and board while studying Wyoming’s geology.

The camp’s reputation grew as did the number of students. In 1948 the camp was renamed the Branson Field Laboratory in honor of its founder. Today the camp is still in operation with students from around the world studying there.

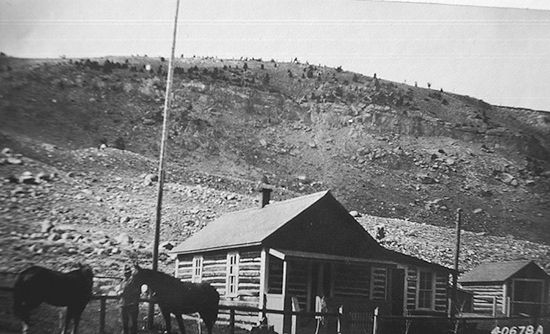

Middle Fork Ranger Station

The upper half of the canyon is part of the National Forest system begun in 1891. The U.S. Forest Service was created in 1908 to manage the national forests and in 1909. The Middle Fork Ranger Station was built in the canyon, an ideal location with access to the forest above the Wind River Valley for rangers and other users of the forest. The original station was a group of log buildings down slope of the road near the river. There was also a bridge spanning the river. The tall wooden flagpole at the side of the ranger’s house let visitors know if he was there. If the American flag was flying he was in, if not he was in the backcountry.

In 1936 the log buildings were torn down and replaced by white frame buildings on the other side of the road from the old site. The buildings served as the ranger station until 1947 when most were removed leaving only one building as a work station.

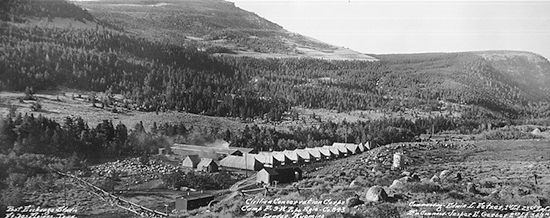

Civilian Conservative Corp

In 1933 at the height of the Great Depression, Civilian Conservation Corps camp F9 was built in Sinks Canyon. It was a large tent camp located downstream of the original ranger station and laid out by officers from Fort Frances E. Warren in Cheyenne, then still a cavalry outpost.

200 men, many from Oklahoma and not used to Wyoming’s cold spring nights, got off a special train at the Lander depot in May 1933 and made the journey to their new summer home in the canyon. The C.C.C. boys were thereto work on the road. Doing almost all of the work by hand with pick, shovel and dynamite, they widened and leveled it from the Rise to Bruces campground, putting a new bridge cross the river at Bruces, and then pushing the road up Fossil Hill. The camp was re-established in 1934 and that summers’ C.C.C. crew continued switchbacking the road up the mountain, cresting it and dropping over to Fry Lake late that summer. The Forest Service had started building a road from the South Pass side and they continued that work until 1940 when they connected with the road built by the C.C.C. completing the Loop Road.

Sinks Canyon Ski Area

Finish line at a race in the 1960s

In the 1950s many county residents began plans to create a ski area in Sinks Canyon. In 1958 after getting permission from the Forest Service the Sinks Canyon Ski Area at the base of Fossil Hill was laid out. Through that fall volunteers cleared ski runs, installed a small warming hut and rope tow and trained a ski patrol. Nearly all of the labor and materials were donated by local people who wanted a ski area near Lander.

Over the next 20 years volunteers kept working on the area, adding a longer rope tow and electricity, new ski runs and a new large warming hut. The new warming hut was a barn donated from the 1936 ranger station and moved across the river on a flatbed truck.

When there was enough snow, the ski area was a popular pastime for residents, but many years there was only enough snow to ski on a few weekends. Lack of snow and money was a constant problem that along with liability issues shut the area down in the 1970s.

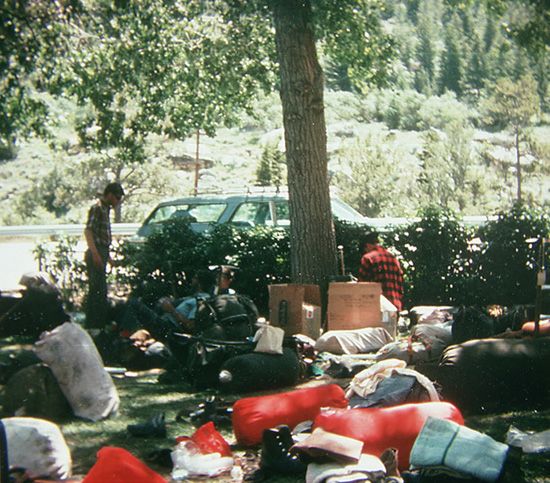

National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS)

In 1965 world class mountaineer Paul Petzold started the National Outdoor Leadership School. The school was designed to train young adults in outdoor survival, minimum impact camping and outdoor and environmental leadership skills. In 1966 the school leased the buildings around the Rise from the city of Lander and moved its operations to Sinks Canyon.

The old power plant was partially rebuilt and used as equipment storage, an issue room and a sewing room to create the special gear the school needed. The two residences were used as offices, kitchens and instructor housing. The old garage was food storage and most of the students slept in tents in the aspens across the river channel from the Rise, having to ford the channel or do a tyrolean traverse of it during spring run-off.

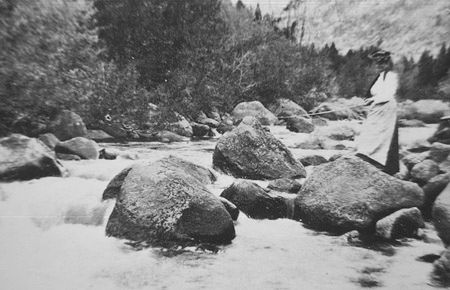

The world famous National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) was originally based in the canyon. Here a student crosses the river on a Tyrolean Traverse to a campsite in the early 1960s.

The school operated out of the canyon until 1970, when it had outgrown the limited facilities available in the canyon. The school moved to Lander where it thrives, educating hundreds of students and becoming the most respected school of its kind in the world.

Sinks Canyon State Park

Over the years many people recognized the unique beauty of Sinks Canyon and set out to protect it. An editorial in 1888 lamented that “…it will be but a short time till Popo Agie Canyon will be located…and made one of the most popular resorts in the west. But then it will lose its present ruralistic attractions and will be so removed from nature that the pleasures of a day will not be such as now.”

Many private individuals and public organizations set out to see that the canyon was preserved for future generations. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department bought large portions of the canyon in 1939 and 1953 to be set aside a wildlife habitat and protect the fishery. A 1939 editorial in the Wyoming State Journal said: “For the purchase price of less than $2.50 an acre the state owns a natural wonder which in Colorado would be fenced off and fifty cents charged to see it.”

In 1963 Pacific Power and Light Company donated the Rise and the seven acres surrounding it to the city of Lander for use as a park and in 1970 city and state officials working with the state legislature and private citizens created Sinks Canyon State Park, the first park created under the newly formed Wyoming Recreation Commission.

The bill creating the park was signed in 1971 and the W.R.C. set out to protect the park and enhance some facilities. A new overlook was built at the Rise in 1972 and the Visitor Center was completed in 1973. Over the next decade many improvements were made all the while attempting to preserve the unique and wild qualities that made Sinks Canyon one of Wyoming’s show places.

The original park development plan probably said it best: “Within the canyon walls are found unspoiled symbols of the best of Wyoming. The mountains, the river, the fish and wildlife; sage, wildflowers, aspen and pine trees, a rugged country of tranquil quiet under blue sky. The development of park facilities must accent and enhance these values. To overwhelm them with chrome plated campgrounds and concession stands would be unwise.”

Today Sinks Canyon still offers special experiences to thousands who visit each year. Visitors form all over the world come to hike, climb, fish, camp or just enjoy the quiet and clean air.

In some ways the canyon has changed, but the timeless beauty, mystery and splendor remain.